The Best of the New DVD Releases of 2019

People just love movies. They are one of society’s favorite forms of entertainment and a great way to experience a story. Documentaries can be instrumental in the spread of new ideas or concepts. Hit movies such as Star Wars or The Godfather can have an economic and cultural impact that goes far beyond the silver screen. As a society, we regularly reference movies and lines of dialogue in our everyday lives.

At one time the only way to enjoy a movie was to purchase a ticket and watch it in a theater, or perhaps watch a censored and cut-up version on television. Today we have a variety of methods that can be employed to watch a movie.

Streaming services are proliferating rapidly and offer uncut and commercial-free movies sent straight to your TV, computer or mobile device. One of the most popular ways to consume movies in your home is to take advantage of the large number of movies on DVD.

Although less popular than today’s online streaming platforms, DVDs are still a viable way to watch your favorite movies in great quality, with the highest resolution being 480i. DVDs come in different formats, including MPEG-2, MPEG-4 or most popularly known as BluRay and MPEG-1. These formats differ in supported encoding method, file size and quality, with MPEG-2s and 4s being the best choices for quality.

It is worth noting that MPEGs were created by the authors of MP4, which is currently the most popular video format used today for its flexibility when it comes to supported devices, compressibility, and overall output quality.

Toward that end, we are going to take a look at what we consider to be ten of the best recent DVD releases. We will be focusing on new DVDs that have been released or that have prospective DVD release dates in 2019. Without further ado, here is our list.

This modern remake of a well-told tale stars musical sensation Lady Gaga and Hollywood star Bradley Cooper. Cooper also makes his debut as a director on this film. Fans of both performers will be very pleased with how they handle their roles and the onscreen chemistry between the stars helps make the story more heartfelt and believable.

Subjects such as substance abuse and the struggle of making it in showbiz are explored in the film. The movie comes highly recommended to fans of love stories and is an example of how new life can be brought to an idea that is as old as humankind. Set to be released in February 2019.

This docudrama about the iconic English rock band Queen and its frontman Freddie Mercury was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture as well as four other categories. The film follows Queen and Mercury as they rise to become world-famous entertainers.

Mercury strikes out on his own in an attempt to pursue a solo career but does not reach anywhere near the success of his former band. The band reunites for what is considered one of the greatest shows in rock history at the Live Aid music festival. This film is an exploration of the idiosyncratic life of a rock superstar whose life was tragically cut short by the AIDS virus. DVD release date – February 12, 2019, so check it out if you are a music fan.

Here is a movie that delivers a message that is pertinent to our time under the guise of entertainment. The film follows the journey of an Italian-American bouncer from the Bronx who is hired to drive a world-class concert pianist on a tour from New York through the Deep South. The pianist is black and the duo must deal with the racism inherent in parts of American society.

They use the “Green Book” to guide them to the establishments that will safely serve a black man in those times. The men form a bond and conquer their differences as they survive the journey. It is a testament to the power of looking beyond the color of a person’s skin to expose the human being within. Set to be released in March of 2019.

Fans of the American political drama House of Cards will be glad to hear that the last season is included in the DVD releases set for March 2019. The multi-season epic concludes with Season 6 in which Claire Underwood becomes President of the United States.

While perhaps not living up to the high standard set in previous seasons, anyone who enjoyed the earlier episodes will be interested in seeing how the tale comes to an end. The series paints a bleak picture that focuses on the underbelly of American political discourse.

Here is another of the new movies on DVD that will find its way into the homes of fans of action and superhero films everywhere. It offers a twist on the traditional superhero movies by delving into the Spider-Verse which is inhabited by a number of different and distinctive Spider-Men such as Spider-Ham and Spider-Man Noir. If you like superhero films or are just a Spider-Man buff, you will be able to buy this DVD starting in mid-March of 2019.

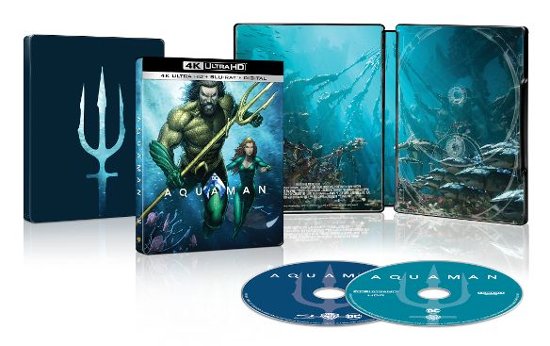

This is the first full-length feature film devoted to this DC Comics superhero who makes his home under the sea. Set for DVD release in late March, the film stars Jason Momoa in the title role and features stars such as Willem Dafoe and Nicole Kidman in supporting roles.

The main storyline concerns Aquaman’s efforts to prevent a war between the underwater and terrestrial worlds. Striking depictions of the undersea kingdom are among the visual treats in store for those who choose to immerse themselves in this story.

Hollywood icon Clint Eastwood produced and directed this taut drama based on a true story. The film follows a man in his 80s, Earl Stone, who has become a drug runner for the Mexican cartels. His age and spotless criminal history allow him to soon be responsible for moving large amounts of narcotics into the United States. It is Eastwood’s first acting gig since 2012 and is set for DVD release in April of 2019.

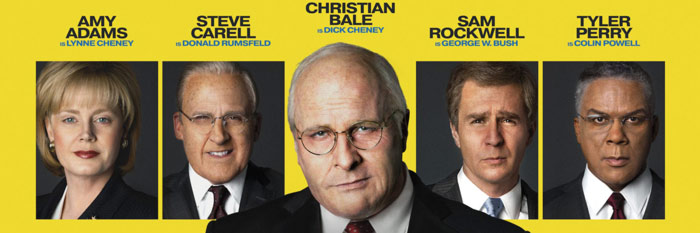

Christian Bale stars in this biographical comedy-drama about Dick Cheney, former Vice President of the United States. It was nominated for an Academy Award for best picture and is a depiction of the man who was to become one of the most powerful Vice Presidents in U.S. history. Reviews are mixed and your political leanings may influence your enjoyment of the film. If you want to get it on DVD, it’s coming out in early April.

While it is too late for this year’s holiday season, consider tucking this DVD away for family viewing next December. It’s an updated take on the Dr. Seuss book that features 3D computer animation to bring us into the world of Whoville.

The movie follows the attempts of the Grinch to ruin Christmas for the Whos. He is supremely disappointed when his efforts only reveal that the true meaning of Christmas extends far beyond the gifts and decorations that he has destroyed. It’s a holiday movie with a message for everyone and you can get it on DVD starting in February.

This period piece focuses on English nobility during the 1700s while England was engaged in a war with France. It features strong performances from actresses Rachel Weisz, Emma Stone, and Olivia Colman and follows the interpersonal relationship between England’s Queen Anne and the members of her court. Those who enjoy historical dramas shouldn’t miss this one which is available on DVD in March in 2019.

This film, based on a 2012 documentary by Max Fisher titled “The Wrestlers: Fighting with My Family,” is a sports comedy-drama that features Dwayne Johnson, Florence Pugh, Jack Lowden, Nick Frost, and Leana Headey. It’s about the life of a real-life wrestler named Saraya-Jade Bevis, a.k.a “Paige.” This movie had wrestling and WWE fans cheering as it captures the struggles of a wrestling professional and how she successfully proved to the world that she deserves a spot on the WWE roster.

A number of popular WWE stars like Sheamus, Big Show, and The Wiz made their appearance in the film, making it a real treat for WWE fans. The movie is set to be released in February 2019.

The movie’s story revolves around a stoner poet named Moondog and how he leads a pretty rebellious life. This comedy film stars Matthew McConaughey, Zac Efron, Jimmy Buffett, Jonah Hill and Snoop Dogg. Despite the comedic and dopey theme, this movie has a good amount of wholesome scenes that lead to Moondog’s self-realization.

This movie is one of Harmony Korine’s best creations. If you’re a fan of goofy movies that features both foolishness and a rich storyline, this movie is for you. It’s set to be released in March 2019.

This film mirrors what goes behind the scenes in the NBA’s Rookie Transition Program. It’s about a sports agent and his efforts to save the careers of pro basketball players after a lockout. However, what makes this movie unique is how its cinematography was achieved with just an iPhone 8. This was made possible with the talent and experience of its director, Steven Soderbergh who also directed Unsane which was also shot with an iPhone.

In the film, you will see a number of NBA players including Reggie Jackson, Donovan Mitchell and Karl Anthony Towns. They will help you get a glimpse of what it takes to become an NBA rookie. The film is set to be released in February 2019.

This film is based on the novel “The Aftermath” by Rhidian Brook. It is directed by James Kent who is also famous for directing Testament of Youth, The Thirteenth Tale and Margaret among many others. The movie is set post World War II, particularly during post-war reconstruction in Germany. The story is about a British colonel and his wife’s experiences with the previous German owner of their temporary residence. The movie stars Keira Knightley, Alexander Skarsgard, and Jason Clarke. It is set to be released in March 2019.

This is a biological drama about James Murray and his friend William Chester Minor who was accused of murder but was found guilty because he was mentally ill. W.C. Minor was a retired United States Army surgeon who ended up in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. This movie, directed by Farhad Safinia, starring Mel Gibson, Sean Penn and Natalie Dormer, tells the story of the book “The Surgeon of Crowthorne.”

The movie is known for its rich depiction of a mid-19th century history and the materialization of the Oxford English Dictionary. The two-hour film is set to be released in May 2019.

Whether you choose to purchase your DVD’s or obtain them from a service like Netflix’s DVD rentals, you are sure to find something you will like in the preceding list. Grab one tonight and relax with a great movie. You’ll feel better when it done, guaranteed!